Marc Shargel's Blog

The Stinky Corpse Flower, A Plant That Imitates Dead Meat

|

|

| When the Corpse Flower that had been cultivated at the UCSC Arboretum finally bloomed on August 1 & 2, 2022, viewers flocked to see it. | |

I took my camera to the Arboretum and wove my way through the crowd to get close to the flower. It was huge! In its pot, the plant stood as tall as a tall man. I braced for the famed stink. It was milder than I’d feared, but I learned it was not at its peak at that hour. Up close, it did smell bad. Corpse Flowers emit an odor like rotting meat or vegetables. Their dark red color simulates blood, and the pale yellow center warms to 98°F when the blossom is ready to produce pollen. Flies can “see” the warmth as their eyes, unlike ours, sense infrared light. The heat also helps disperse the flower’s stench. All three tricks, the smell, color and heat, fool flies into entering the flower and then crawling deep inside where the pollen lies. They think they’re headed toward dead meat, a place to lay eggs which will hatch to produce maggots, which become flies. But instead of finding dead meat they discover they’ve been fooled, only to emerge coated with Corpse Flower pollen.

|

||

|

At the UCSC Arboretum, I learned from Director Martin Quigley that the Corpse Flower grows in the wild only on western Sumatra island in Indonesia. There are less than 1000 believed to survive in the wild, and about 100 in cultivation. Interestingly, its habitat is largely the same as that of the Sumatran Orangutan, whose wild population also numbers about 1000. So both are critically endangered species. The Corpse Flower is sometimes called the world’s largest flower, and it is the largest bloom, but it is not truly a flower. Botanists call it an “unbranched inflorescece” which is many flowers on a single stem.

As I sat to write this story, I discovered a personal connection to the Corpse Flower I hadn't even realized. I mentioned that the plant had been carefully cared-for at the Arboretum for about a decade before it bloomed. I didn't know that one of its care-takers has been my old friend Jim Velzy. I've known Jim for perhaps 30 years. Jim retired as keeper of the UCSC Greenhouses a few years ago. I learned in this article that he'd had a lot to do with nurturing the Corpse Flower. Thanks, buddy!

|

||

|

||

The UCSC Arboretum receives no funding from the university. It is supported exclusively by donations from the public, like us, and is staffed largely by volunteers.

* ”Lagniappe” is a French Creole word I learned in New Orleans. It means a “little something extra” like a free taste of appetizer upon seating in a restaurant. This set of photos went out days before release to the general public as a lagniappe for my valued Patreon subscribers. Thanks!

Kelp Forest Restoration Project Exceeds Goals

|

|

| A volunteer diver culling urchins at Tankers' Reef. |

Sea urchin populations in much of California are now as high as 500 times what they were a decade ago. Since 2013, an important urchin predator, the Sunflower Star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) has gone locally extinct. Urchins have emerged from hiding and multiplied to feed on algae of all kinds, but especially Giant Kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera). As urchins gnawed kelp near the seafloor, the huge floating forests of kelp drifted away on the current, and with them California’s richest ecosystem. Divers and fishermen were alarmed at the reduction in marine life and biodiversity.

Keith Rootsaert, the founder of G2KR, petitioned The Fish & Game Commission three times for permission to cull urchins in an attempt to protect the remaining kelp and give new plants a chance to grow. Backed by overwhelming public support, part of the third petition was finally given a green light in December of 2020. The Commission laid down criteria for success: reduce the density of sea urchins on an experimental area to less than two per square meter, cause no other significant impact to marine life, and stay safe. A leadership team settled on a carefully designed urchin culling procedure, using a lightweight hammer and ecologically sensitive diving protocols. They also created a data reporting procedure. By late April of this year, team members led by Marc Shargel designed a training class for Kelp Forest Restoration specialty divers. A dozen area scuba instructors learned to teach the class and certified divers can now be certified by NAUI or PADI as Kelp Forest Restoration specialists. As of November, 2021, 63 divers have received that certification. All the divers are volunteers and some of the instructors have donated their time to train them.

In less than a year, G2KR has signed up 356 supporters, created extensive online facilities to manage the volunteer effort and gather dive data, and logged 424 dives for the project. There has been a total of zero injuries or diver emergencies.

The project’s criteria for success were to self-organize, stay safe, and avoid incidental damage while reducing urchin density to below two per square meter. At some dive sites on the Monterey Peninsula as many as 30 can be found on a one-meter patch of the bottom. Volunteers from Reef Check California, led by Dan Abbott, marked out a target grid of 2.5 acres, and did urchin abundance surveys there, and on a control area, before and after volunteers culled urchins.

Urchin density on the test grid was about seven per meter before the trained divers went to work. Afterward, it was barely over one. With training, volunteer specialists were efficient at culling urchins and extremely careful not to disturb any other life. Observations of incidental damage are insignificant thus far, though more fine-scale assessment is planned. One diver self-reported “I touched the bottom with my finger once, and it will never happen again.”

| Registered Supporters: | 356 |

| Divers Trained: | 63 |

| Divers Reporting Data: | 67 |

| Number of Working Dives: | 424 |

| Diver Injuries or Emergencies: | Zero |

Meanwhile, intrepid volunteers accessed the project site via the beach. There are only eight parking spaces near the site, just of Del Monte Blvd in Monterey. Those can’t be occupied for long enough to do a dive on weekdays, so volunteers worked on weekends. The route from parking to test grid is 850 yards, about half a mile. Divers traversed that distance to get to the grid, then again to get back to cars, carrying about 80 lbs of dive gear per person.

Some instructors chose not to take their Kelp Forest Restoration students on the arduous beach route, and waited to teach classes off the boat. At least 37 new volunteers waited all summer and may start training soon at last.

Some of the instructors who did conduct classes from the beach received a “Cease and Desist” letter from the State Department of Parks and Recreation. The beach onshore from the project site is Monterey State Beach, administered by that department. The letter said scuba instructors had to have a state parks concessions permit to take students across that state beach. That despite the fact that scuba classes have used state beaches throughout California for decades. The “Concession Proposal Workbook” sent by the Chief Ranger runs 16 pages. The requirement was ultimately dropped.

While working through these obstacles, G2KR’s Rootsaert and Shargel have forged excellent working relationships with partners at CDFW, the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and the California Ocean Protection Council. The principals meet about twice a month, to share data, plan strategy and optimize the scientific value of the project’s outcomes.

Keith Rootsaert has just submitted a fourth petition to the Fish & Game Commission, asking for permission to expand the giant kelp restoration project into three State Marine Conservation Areas (SMCAs) where the majority of recreational diving in the Monterey area is done. A proposal to try to save kelp forests in one of those conservation areas has been a part of each of the three previous petitions, denied each time. Hook-and-line fishermen have always been as free to catch fish in those SMCAs as any other part of the ocean. But the commission contends that urchins, because they are a native species, should be left undisturbed in those areas. The state has no project of its own to stop or even slow their onslaught, and the commission has given every indication that it will not allow volunteers, no matter how well trained, to defend the giant kelp that remains within the SMCAs.

Vehicle Attempts Scuba Dive Without Driver

|

|

| Photo of my van in Monterey Bay, courtesy of hero-of-the-day Hunter Richardson of Monterey Bay Scuba. |

Another diver who witnessed the catastrophe alertly reached into the van and saved my iPhone from certain death. Thanks, Royston! The van itself emerged from the Bay a few minutes later due to the heroic appearance of Hunter Richardson, proprietor of Monterey Bay Scuba. Hunter put his pickup truck in position to pull my van up the ramp, I shouted to another by-stander to fetch my boat-tow rope off the boat and Hunter plunged into the chilly water to tie the rope to my undercarriage. His pickup and the rope pulled the van about halfway out of the water before the weight of van+seawater snapped the rope. I put on the parking brake, we tied on a second rope and made it up to the parking lot at last. In addition to Hunter's prowess as a vehicular marine rescue expert, he and his father John Richardson are really nice people and I encourage you to patronize their dive shop at the Breakwater.

On dry land, the van looked like a cross between an aquarium and a post-flood disaster area. There was still about a foot of saltwater draining from the cargo well. Five stinging sea nettles had washed inside. Ryan, the third member of our would-be dive group put on his gloves and kindly scooped them out for me. I looked in vain for my wallet, which I was pretty sure I'd left on the passenger seat. The van's electrical system was so ruined that I had to disconnect the battery to stop the horn from blowing. Knowing the van would not move under its own power I called AAA. They asked for my member number. I promised to give it as soon as my wallet (with my membership card) came back from the seafloor. No number, no tow truck is their inviolable rule. The friend who'd driven the van into the Bay donned scuba gear and walked down the ramp. Many objects had washed out: countless paper maps began to decay in the water, creating a lot of visual distraction. But in the course of about 40 minutes many things were returned to the dock: a shirt that had drifted between some piling, a bit of ruined electronics for my iPhone, and finally my wallet and a stray credit card.

|

|

| Just over a month ago I became the owner of this 2003 Tacoma 4WD pickup. It has proven to be a fine tow vehicle on its first outing. |

In early February I bought its successor, the old but super-clean Tacoma 4WD pickup you see here. I replaced the old cassette stereo with a modern one that includes a backup camera for hitching to the boat trailer. I had the trailer wiring socket improved and upgraded the headlights. It works great, and on its first dive trip everything went fine on the ramp. I did all the driving though.

Urchin Culling Experiment Approved for Tankers' Reef, to Begin April 2021

|

|

| At the base of "Marco's Pinnacle" in Point Lobos State Marine Reserve, rocks are overrun with Purple Sea Urchins, which have eliminated the kelp that once grew there. Get the details on my website. |

At the August 19 meeting of the California Fish and Game Commission, after about two years of citizen requests, the Commission approved half of a petition asking for permission to cull urchins from a small area of seafloor, in order to demonstrate that urchin removal can foster kelp recovery. Since 2013 urchin populations have exploded—one authority says by 500 times or more. Urchins eat kelp, and all along the Monterey and Pacific Grove shoreline, kelp forests are disappearing. Some are gone altogether, giving way to underwater deserts, while others being transformed into a different kind of ecosystem.

Special thanks are due to everyone who spoke to the Commission or wrote letters of support for the petition. You made it happen. I have no doubt that without all your support we wouldn't be here yet.

The Commission granted permission for citizen-scientist divers to cull urchins by crushing them underwater in a small area to the east of the Monterey harbor. That is half of what was requested: another small area to the west of the harbor was proposed as a second study site, but that was denied because it is inside a marine protected area (MPA). The commission's logic on that is difficult to discern. Throughout the state they have consistently denied citizen requests to remove destructive plants and animals from ecosystems inside of MPAs because the MPA status gives them legal protection. That's despite the undisputed fact that they are smothering the native life. In Pacific Grove a small marine reserve that previously held a thick forest of giant kelp is now bare. A thousand or more species that used to live there are gone, replaced by a carpet of sea urchins. At Catalina and Santa Cruz Islands, similar kelp forests are also gone, replaced there by an invasive seaweed. Reef-Check diver Keith Rootsaert, who originated the petition, says, "the MPAs were not intended to be a suicide pact." As a participant in their creation, I couldn't agree more. In Southern California, marine biologist Nancy Caruso is petitioning for permission to remove the invasive alga smothering kelp there. That petition is still in process, and needs our support.

The Commission's action gives Central California divers work to do. The regulatory change will become effective in April, 2021. At that time we'll be legally allowed to cull urchins from an area known as Tankers' Reef, a shale reef off Del Monte Beach in Monterey. We have until then to organize and learn proper procedure for carrying out the task. Keith Rootsaert and others will be distributing materials and information via Keith's list and local dive shops. I'll provide links in future editions of this newsletter. You can get onto Keith's list at g2kr.com.

But our work at the commission is not finished. As mentioned above, they've steadfastly refused to allow any type of direct action to protect or restore kelp inside of MPAs. That's a real worry, because all of the popular and accessible dive sites from Monterey to Big Sur are inside of one MPA or another. Unless we can work out some kind of reasonable policy for MPAs, divers will be forced to watch those kelp forest ecosystems disappear, or become criminals to save them.

You can learn how this situation came about in my blog. You can read about the impact of the Commission's refusal to adopt the other half of the petition in a previous newsletter. And as I mentioned, you can stay informed about how to make a hands-on contribution to the project by reading future additions of this newsletter and by signing up at g2kr.com.

Urchins Destroying Monterey Area Kelp Forests: Update and Action Plan

This article contains information also available in the video of Marc's presentation Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, recorded on Friday, May 8, 2020. See LivingSeaImages.com/voyage. Since I first alerted my readers to the disturbing sea urchin outbreak in 2015, things have gotten worse, and governmental response has been to prevent conservation efforts. But Monterey-area divers have an action plan.

I began writing about this disturbing phenomenon in a2015. In the last year, we’ve learned more about it, discovered deeper mysteries, and some citizen-scientist divers have offered to try to help. As of this writing, the Fish and Game Commission refuses to allow their volunteer efforts to proceed, research is minimal, and things have only gotten worse.

|

|

| A dying Vermilion Star photographed in British Columbia in August, 2014. | |

Why, you ask, are we talking about sea stars? Because we now believe that one specific kind, the Sunflower Star, had been an important control on urchin populations, preventing the kind of upending of ecosystems that we’ve been seeing.

|

||

|

||

Now in 2020, seven years after the onset of sea star wasting, most species have made a come back. I’ve been seeing Giant-Spined Sea Stars, Ochre Stars and Bat Stars on rocks off the Monterey Peninsula again. The ever-multiplying urchins seem not to mind them a bit. On a recent dive along the shore of Pacific Grove, I found urchins nestled cozily between the arms of a Giant-Spined Star. Two Bat Stars were nearby. In the last year, a new cohort of juvenile urchins has settled in among their parents.

Why then, do things not seem to be returning toward a more "normal" balance of life? What will it take to curtail the explosion of urchins and give our kelp forests a chance to recover? So far, still missing from the sea star recovery picture is the top predator of Central California’s invertebrate world: the Sunflower Star, Pycnopodia helianthoides. If the Sunflower Star were a shark, it would be a Great White. It is huge, reaching more than a meter in diameter. It is voracious, feeding on the spiny urchins, other stars, snails and even relatively huge abalone. It is fast enough to chase down and overtake any of them. As ecologists have learned, top-level predators like the Sunflower Star have a tremendous influence on the entire web of species they are a part of. But I haven’t seen a Sunflower Star in years, and no diver or marine biologist I’ve consulted has either.

|

|

| Three purple urchins and one red urchin nestle comfortably near the arms of this large sea star. We’d hoped the return of various stars would begin to control the urchins. | |

We used to believe that Sea Otters would prevent urchins from multiplying out of control as they do now. Sea Otters definitely fed on urchins in the past: as a college student and new diver in 1978, I watched a brave otter take a tasty urchin from the hand of a classmate and bite right through it, spines and all. It clearly regarded that urchin as a prize. But research of PhD candidate Josh Smith, at UCSC, has shown us that otters don’t eat urchins in an urchin barren. And research by Reef Check divers explains why. Urchins packed this densely have chewed away all the good food: they’re emaciated. An otter has to expend more energy to dive for one of these urchins and eat it than it would get back in digested calories. Smith’s research show us that otters do still eat urchins in healthy kelp forests, where the urchins are presumably well-fed and worth eating.

So, Sea Otters are not controlling the urchin explosion. Which brings us back to the Sunflower Star. That keystone species has not begun a recovery. Some biologists began to call them locally "endangered" and more recently even "locally extinct." Human intervention may be the only hope to maintain what little giant kelp forest remains in Central California, or to restore what’s been lost. Reef Check has a well-organized program underway in Mendocino County and has even gained modest state funding. But attempts to mount a similar project in Monterey County have been blocked by the California Fish & Game Commission. They have so far refused to change the law to allow citizen-scientists to remove urchins in the quantities necessary to even develop a protocol that could save giant kelp forests.

So we're going to have to apply political pressure to prevent citizen-scientists from being cited or arrested for trying to save kelp forests. We'll need your help. Please contact me and also sign up for the "Giant Kelp Restoration Project" newsletter.

Even if a kelp restoration protocol can be devised, it will then need to be scaled up dramatically. How much can a small group of human beings, motivated by goodwill rather than profit, do to restore an ecosystem? Some biologists are suggesting we should attempt to breed and restore Sunflower Stars. But mankind has never accomplished that feat either.

|

||

|

||

Concerned divers who want to do what they can to control the urchin explosion should contact me and also sign up for the "Giant Kelp Restoration Project" newsletter. Both sources will keep you updated on developments and notify you when we can legally begin urchin clearing experiments. The"Giant Kelp Restoration Project" is being led by Keith Rootsaert, who is a Reef Check marine science co-ordinator and a Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council Diving Representative. Keith will be orgainizing a team to organize divers to remove urchins from two areas near the Monterey harbor. To keep updated on current developments, you can sign up for the newsletter on the Giant Kelp Restoration Project website.

My Year in Photographs, Coming to Open Studios

I'm already gearing up for the 2019 edition of Santa Cruz County Open Studios. I’m looking forward to sharing stories and photographs from recent travel to Iceland and underwater adventures of the last year. I went back to Iceland this past July and found an amazing sea bird rookery. Atlantic Puffins were watching chicks emerging from their underground nests. There were thousands of these amazingly colorful birds packed into a tiny area. The Puffins were so dense on the top of that little island that I could get more than a dozen in one photograph. The Puffins were nesting in the sod on top of a tiny, rocky island called Hafnarhólmi, near the village of Borgarfjörður eystri. Those names don't roll easily off the tongues of English-speakers; Icelandic takes some getting used to!

|

|

|||||

| Colorful adult Puffins watch a monochorme youngster emerge from its underground nest. | A small cluster of Puffins were among thousands on Hafnarhólmi island. |

|

||

| Two Kittiwake families nesting on the sheer rocky cliffs below the soft earth favored by Puffins. |

The sides of Hafnarhólmi island are sheer, vertical rock. Right below the Puffins on those cliffs, Kittiwakes were nesting. These seabirds are gray and white like gulls, with a slender yellow beak. Their downy chicks were huddling close to the parents, begging to be fed. Any ledge in the rock became a spot for a Kittiwake nest. In some places they were stacked as closely as rungs on a ladder.

Sea birds are just one type of wildlife I've photographed over the last year. There will be plenty more to see at Open Studios.

|

||||

|

A couple days later I visited Gulfoss (Gold Falls) on Iceland’s Golden Circle route, which is heavily traveled by tourists. As I approached an overlook, the sun emerged from clouds and a rainbow erupted in the mist rising from the falls. I’d been to these falls about a year before, on a gray day where they looked impressive, but not nearly as beautiful. This view featured the full spectrum of color in the rainbow, with vibrant greens repeated in the grass, blue in the sky and all framed by the deep gorge of the falls. I shot quickly, knowing the rainbow might disappear at any moment. I go my shot, less than five minutes before another cloud obscured the sun.

Iceland is so amazingly full of waterfalls that I couldn't tell you how many falls I photographed on the trip, or how many I noted without even shooting them. Some we stumbled upon withot even knowing they were on our route. Those were among the best, like finding an unexpected easter egg. I'll have photos of lots of falls on display at Open Studios (some printed, most projected.)

|

||||

|

Earlier in the summer I did a dive expedition down the Big Sur coast. It was a lovely trip, but my most rewarding underwater photograph of the year was taken very close to home, along the Pacific Grove shore. At a deep dive site I visit often, I found a fish seldom seen in California, the Grunt Sculpin. It is a tiny and odd-shaped fish that could nestle in the palm of your hand. I’ve seen them far to the North in British Columbia, but in forty years of diving, never in California. So I got my camera into a comfortable position on the bottom, 95' below the surface in the 51°F water, and fired off dozens of frames of this unusual little critter. Am I a marine science nerd to be so excited by this rare encounter? Absolutely. But don’t you think he has a little charm?

Visit Open Studio #154 in Felton on the first or third weekend in October and see how much charm you can find in Marc Shargel’s images of wildlife and natural subjects.

Shared Adventures' Day on the Beach

|

||||

|

On July 14, I didn't go diving. I didn't even celebrate Bastille Day. I braved the crowds and went to Cowell's Beach, at the foot of the Municipal Wharf in Santa Cruz. Why? A very special bunch of people were there, organizers from Shared Adventures, an army of volunteers like me, and many disabled people and their families from all over Northern California. It was Shared Adventures' annual day to make it possible for folks who can't usually go kayaking, scuba diving, or just roll around on the beach to do those things.

I paddled a tandem kayak from the beach out to the kelp bed near Steamer Lane where a group of Sea Otters were waiting for me and my passengers. I made five trips, in turn carrying carrying two autistic boys, a teen with Down's Syndrome, a blonde girl of about 10 who never spoke but smiled the whole time she was in the boat with me, and one woman who was paralyzed below the waist. My first passenger was an autistic teen, close to my own son in age. He couldn't use his paddle but loved to hold it down in the water and watch as the water flowed around it. Of course he was creating a sea anchor, but I figured that his enjoyment of seeing the pattern it made in the water was exactly the kind of experience we were trying to create. So I stroked a little harder and all had a good time.

This was my third or fourth year volunteering as a kayak guide. It's always a full day, and this one was especially full with five trips, plus haulling extra gear that the organizers said they needed. I was very tired at the end of the day, but as I have every year that I have volunteered, I came away happy knowing I had given a few people a reason to smile.

With the amount of traveling I do, I can't be sure where I will be when next year's Day on the Beach comes around, but if I'm in town I will probably volunteer again. If you'd like to share in the fun and good feeling, perhaps you would like to volunteer too.

The Dark of the (Super Blue Blood) Moon

|

|

| A composite time lapse of the Lunar eclipse, digitally placed above an image of Natural Bridges State Park taken as the first rays of the sun touched it at dawn the same morning. |

A few months after my adventure to see the total eclipse of the sun, I heard about another total eclipse that would be visible from near my home, this one of the moon. I set an alarm for just after 2am on Wednesday, January 31 and drove to a hillside overlooking the ocean near UC Santa Cruz. I hauled my tripod, camera, and telescope-like 600mm lens far enough from the road that headlights were unlikely to ruin my photos, and by the time I got set up the eclipse had begun.

I stood out in the chilly pre-dawn air while the moon passed through the shadow cast by the earth. Unlike an eclipse of the sun, the eclipsed moon is not blacked out by an object passing in front of it; it slides into the soft-edged shadow cast by the Earth. And a little light, reddened by passing through the Earth's atmosphere, falls on the moon even at totality.

While the eclipsed moon is sometimes called the "Blood Moon" because of its red color, the lunar eclipse of Jan 31 was actually blue. This bears some explaining: it was not blue in color, but lunar eclipses only happen on the full moon, and the full moon of that night was the second full moon in the month. And any time there are two full moons in one calendar month, the second one is called a "blue moon." Blue moons are rare (they average about once every 32 months) hence the old phrase "once in a blue moon."

Why was this a Super Blue Blood Moon? Well, that's becasue this full moon and eclipse also co-incided with the closest approach of the moon to the Earth, in the moon's not-quite circular orbit. The moon gets about 5,000 miles closer to earth at perigee, it's closest approach, than its average distance. But have no fear, even at perigee its 223,068 miles away. The moon at perigee is called a Super Moon because the closeness causes it to appear super-big. But the maximum observed size increase is just 14%. I have photographed super moons twice and, to be honest, can't detect a size difference by eye.

|

|

| A cloud passed by the partially eclipsed moon as it was emerging from the earth's shadow. |

As the moon emerged from the Earth's shadow, it also slid behind the horizon to the West. The sky was lightening to the East as dawn approached. I hiked my camera gear back to the car and made a quick trip down to Natural Bridges State Park where I thought I might get a good view as the early light bathed the one remaining arch in orange light. I wasn't disappointed. After a few hours work in Photoshop, I put together nine images in a single composite (above) showing all the phases of the eclipse over the natural bridge. Unlike the sister image composite of the solar eclipse over Mount Hood, all nine photos were taken within a few miles and a few hours.

In case you were wondering, "The Dark of the Moon" is defined as a period, such as a new moon or cloudy night, when moonlight is absent. I recognize the phrase as the name of a play that was performed at my summer camp decades ago. It is a story of passion and magic, adapted in the 1940s from a very old folk tale and ballad.

Mid-Day Darkness

|

|

| A composite time lapse of the eclipse, digitally placed above an image of Mt. Hood that I'd taken long before. |

Twenty-five years ago, my wife traveled to Hawaii specifically to witness a total eclipse of the sun. She was frustrated by the only overcast day they'd had in Kona in weeks. We began planning to observe the total solar eclipse of August 1, 2017 literally years in advance. I did online research on photographic techniques and equipment. She arranged to rent a camper trailer for us to sleep and cook in.

Two of our long-time friends worked at NASA for years, doing research astronomy. They mapped the "path of totality" where the eclipse could be observed. They overlaid that with maps of typical cloud cover, then checked where totality and clear skies could be seen from public land where we could camp. We ended up planning to head for central Oregon.

Smoke from wildfires forced a quick revision of our camping location farther eastward, and we ended up in a meadow at 5,700 ft altitude in the Ochoco National Forest, about halfway between Mitchell and Dayville, Oregon. If you aren't familiar with those names, I'm not surprised. Each of those little towns has fewer than 1,000 residents and probably hadn't seen visitors in the numbers drawn by the eclipse ever before. Our campsite was 5 miles distant from the relative civilization of a pit toilet. |

||||

|

I set up two cameras, one with a very long 600mm lens I acquired just for the event. I made solar filters for both cameras, so I could record the phases of partial eclipse as the event progressed. I assembled those images into a composite time-lapse you can see above.

During totality, I had both cameras firing away, changing exposure automatically. It was the most sophisticated use of the automation built into my digital cameras I’ve made so far. It was well worth the effort. In the brightest images I can see the sun’s glowing corona extending out into space. But in the darker ones I can clearly see solar flares or “prominences” bursting from the surface. You really should see this image enlarged, though, to appreciate all the detail.

|

|

| The Milky Way as seen two nights before the eclipse. The pine tree at right was "painted" with the light of a distant flashlight for less than 10 seconds. |

My son (who was 14 years old and entering high school just days after the eclipse) and I recently got a great lesson in photographing the Milky Way from a friend. The complete darkness in remote Eastern Oregon gave us an ideal night on Saturday before the Monday morning eclipse to practice our new techniques. We would have had a second night on Sunday, but smoke from the wildfires far to the west blanketed our camp as the sun set, and was just clearing from the eastern sky as the sun rose on eclipse day. I was very worried that all our careful plans and days of road travel might be wasted because of the smoke, but by the time the eclipse began it was almost imperceptible directly over head. We made good use of our single night with the Milky Way glowing above our heads. It took about 30 seconds to make each exposure. While the camera's shutter was open, I used a weak flashlight to “paint” light onto the single pine tree in the meadow we were camping in.

My son captured what I think was an even better composition. He printed his shot and put it on display at my Open Studio!

Fire on the Mountain

|

||

| Smoke billows upward from Loma Prieta Peak at 3:35pm on Sept 26, 2016 about 45 minutes after the first report of fire. |

I began to hear the lyrics of an old Grateful Dead song in my head soon after new intern Michael pointed toward Loma Prieta peak on the afternoon of Monday, September 26, and said "It looks like there's a fire over there."

Fire indeed: there was a huge fire on "my" mountain, Loma Prieta. The column of smoke was enormous and growing. Within a couple hours it spread across a large portion of the ridge. It was clear even from a distance that the fire was growing rapidly. Weather conditions were ideally conducive for a conflagration. Temperatures were in the 90°Fs at my house and probably near 100°F (38°C) where the fire was burning on the ridge.

Smoke dominated a large sector of the sky for about three days, as viewers looked upwards from Felton, Scotts Valley Los Gatos, and points south all the way to Morgan Hill and beyond. It took two days for a small army of firefighters, aided by at least six aircraft to begin to get the fire under control. It is only thanks to these heroes that the damage to structures was minimized. As it was, hundreds of people had to evacuate, about 4500 acres burned. Remarkably, only 12 homes were destroyed.

|

|

| Flames light up the smoke cloud above the ridge at 1:25 AM, less than 12 hours into the event. |

Recent coverage in the San Jose Mercury News and also the Santa Cruz Sentinel repor the fire as close to fully contained as of October 4.

Several concerned friends emailed to inquire if we were in any danger. No, never from this fire. It was about 14 miles (22km) from us and fouled our air only briefly. But every time there is a wildfire in the area, I go out to recheck for dry, dead wood and other potential fuels on my property. Living in a wooden house in fire country is risky business.

Readers of a certain age will remember that Loma Prieta gave its name to a much larger disaster about a generation ago. That was the Loma Prieta earthquake of October 17, 1989. I didn't get home until three days after the main shock, and still recorded some startling photographs.

After 20 Years, I Get Back to the Galápagos

|

||

| Whale Sharks are one of the featured animals in my Galápagos video. |

I am just back from an expedition of three-weeks duration to the Ecuadorian cloud forest and the “Enchanted Archipelago” of the Galápagos Islands. Charles Darwin was inspired to develop his theory of evolution when he went to the Galápagos in 1835. When I went in the 1990s it was the best dive destination I’d ever visited. After 20 more years of exploring Earth's oceans since then, I’ll still call the Galápagos the best I’ve seen, maybe the best on Earth.

In two weeks there I watched children snorkel with cavorting sea lions, saw schools of silvery jacks and barracuda swim by me, watched eight-foot hammerhead sharks cruise along coral reefs by the hundreds, and got up close and personal with endangered green sea turtles. After stepping over hundreds of marine iguanas on a trail away from the beach, I spent a blissful half-hour on a cliff top, watching a blowhole along a shore of lava rock erupt as ocean waves rose to pressurize a narrow opening. Above the blowhole I saw albatrosses, whip-tailed tropic birds and masked Nazca boobies in flight. For a wildlife lover, it is difficult to imagine anything more thrilling.

And then I had an experience underwater that eclipsed all of that—almost literally. As I clung to a reef 65 feet below a natural arch of rock named for Charles Darwin, an enormous shape cast its shadow upon the ocean below. Instantly I launched myself into the current, camera in hand, kicking my fins as hard as I could to converge with this slow-swimming giant. The spotted pattern of a whale shark resolved as I drew closer. As the gentle behemoth swam effortlessly by me I saw first the head, then the pectoral fins, the long body and finally the powerful tail, sweeping slowly from side to side, the tail alone taller than a tall human. The whale shark was so long—about 40 feet—that it took over half a minute to pass by me, like a slow train. In a day and a half of diving under Darwin’s Arch, I had 10 whale shark encounters, and saw an array of large fish and other sharks that would be the main draw anywhere else in the world.

|

|

| Green Sea Turtles, globally endangered, were another highlight of Galápagos waters. |

My main activity during all this action was to capture artful photographs of what I was seeing, but as I did that I often had my little video camera rolling. I've assembled a series of clips into a video of just over five minutes. You can see it here.

Several times since I got back I've been asked for an assessment of the condition of the marine ecosystems I saw. I am glad to report I could not perceive, in a quick glance, any degradation compared to what I saw 20 years ago. Hammerhead sharks still school by the hundreds at the northern islands; endangered green sea turtles gorge themselves on algae that grows on the reefs; whale sharks which are being slaughtered senselessly in other parts of the world glide care-free beneath Darwin's Arch. Of the three major threats to marine life worldwide—global warming, pollution, and over-fishing—the Galápagos are relatively protected from two. There are two main population centers, each with about 20,000 residents, an airport and a seaport. Other than air, land and sea transportation, there are no heavy industries. So pollution would appear to be fairly light. Ecuador has instituted a set of marine protected areas throughout the islands, and banned industrial fishing throughout Galápagos waters. The most destructive of heedless fishing practices, such as shark finning and unintended but lethal netting of dolphins and turtles, are minimized or eliminated. With pollution and fishing relatively controlled, the Galápagos, based on my very brief and unscientific observation, seem to be in better shape than much of the planet. And so I celebrate.

But there is still cause for concern. No local conservation measures can stop global warming. Last year's El Niño, which was probably amplified by global warming, decimated Galápagos Penguins and caused many other changes. While the ecosystem should be able to return to its previous point of balance over several "normal" years, warming may also be causing El Niño years to become more frequent. The latest research suggests that areas protected from other threats, like pollution and overfishing, have a better recovery from perturbations like El Niño. And the Galápagos have extensive marine protected areas. But the Galápagos system of marine protected areas contains huge "exceptions." In the California system of marine protected areas, on which I worked directly from 2000 to 2007, a "marine reserve" prohibits all take of anything alive and alteration of habitat. In the Galápagos, local residents fish for food to feed the populace, and also to feed visitors, such as myself. I was told that the Galápagos tourist industry current hosts about 200,000 visitors a year. This fishing for local consumption goes on within the Galápagos “marine reserve.” Inside the "marine reserve" there is a more fine-grained designation of areas, akin to zoning. Most of the reserve is open to this local fishing, smaller areas are designated for tourist use only, and an even smaller proportion of areas excludes fishing and recreational use for research purposes. And as I mentioned, enforcement of all these boundaries is minimal. But despite all these exceptions and qualifiers, the system seems to be doing its job fairly well so far. Of greater concern, at least to me, is what happens in the future as the resident population of the islands grows further. Twenty years ago when I visited, there may have been only 10,000 to 20,000 permanent residents. Recent government statistics claim the current population is just over 26,000. But this is commonly understood to be wishful thinking. The two main towns in the islands are each home to 20,000 people. There is a third, smaller town and more people living on rural ranches over much of the two most populated islands. A long-time resident and tourist guide told me a more accurate number is somewhere above 40,000 permanent residents. Despite a 1998 law that theoretically halted immigration from the mainland to the Galápagos, free migration has no practical limits. The enforcement budget for that law does not exist, local police do not have authority to deport people who came from the mainland "temporarily" but never left. So the local populace continues to swell, and with it comes all of the impact humans have everywhere. In practice, I believe that the real control on environmental degradation in the Galápagos is the extraordinary economic value of the tourism industry, which is driven entirely by the extraordinary wildlife that lives there. I think that only when that wildlife looks, to tourists like me, under threat, will more binding limits be instituted.

Video Featuring some recent highlights, including Central California

|

||

| Lush Hydrocoral grows in a spectrum of subtle pastel colors on the deep seafloor at Schmieder Bank. |

Before I packed up for the Galapagos, I had already had a pretty good year of diving closer to home. El Niño brought warmer-than-usual water to Central California for the second year in a row. Sadly, the much-needed greater than normal rainfall that often accompanies El Niño did not arrive. But the tranquil weather enabled me to make a return to what I believe to be the most spectacular dive site in California: an isolated, barely-reachable patch of ocean four miles off the Big Sur coast called Schmieder Bank. The bottom there is a carpet of delicate and slow-growing California Hydrocoral in shades of pink and lavender. Fat lingcod seem to be everywhere, and clouds of rockfish hang just above the bottom. But the dive isn't for beginners. The depth is right at the edge of recreational diving range. Many divers, including me, carry an extra cylinder of breathing gas in case something unexpected happens more than 100 feet below the surface.

But a deep dive at Schmieder Bank is an opportunity I would not miss, despite the extra equipment it requires. Nowhere else is the Hydrocoral quite so lush and colorful. I will have images from my descents onto Schmieder Bank this year and last year on display during Open Studios.

|

|

| This is a nice photo of a Blue-Banded Goby, taken in Southern California where they "belong." On April 27, 2016, I shot one in Monterey. |

When El Niño pushes warm water up against the California shore, marine life usually seen farther to the south tends to follow. Last April (the 27th to be specific) while diving on a site called "The Barge" in Monterey, I saw and photographed a fish I had never seen north of the Channel Islands. It is the blue-banded Goby, a tiny fish whose splash of color is sure to catch one’s eye. I couldn't believe my eyes when I spotted one this far north. But I have photographic evidence to prove it.

|

|

| Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola) were a highlight of the fall of 2012. They appear, along withDolphins, Orcas, Octopi and more in my new California/Pacific video. |

I gathered clips from my video captured over teh last four years and put them into another short piece. In just over six minutes you can follow me on marine adventures in Monterey Bay, Carmel Bay, Fiji, and British Columbia. You'll go boating with Dolphins and Orcas, and dive with Ocean Sunfish, Octopi, Lingcod, Egg-Yolk Jellies, Wolf Eels and several kinds of Rockfish.

A Great Audience and Some Great Ink

|

|

| I photographed this scarce Canary Rockfish in the recently-expanded Point Lobos State Marine Reserve in September 2012. At that point it had been living in protected habitat for five years. It may live to more than 80 years old. |

On March 23, 2016 I gave a talk at the Felton Branch of the Santa Cruz Public Library. The title of the talk was, How a Regular Guy from Felton Helped the State of California Heal the Pacific Ocean, and Ended Up in the Book Business. Pretentious, yes, but entirely true. The evening was a benefit for Felton Library Friends, a community group working to relocate the library into a new building from its current cramped quaraters, a church built in 1893.

Every seat in the room was filled as I described how my underwater observations led to advocacy for the creation of marine reserves, then to political action and finally to creating books to illustrate what I had been talking about.

One member of the audience was there reporting for the Santa Cruz Sentinel and a very nice article resulted. The reporter, Kara Guzman, asked thoughtful questions and the resulting piece gave a good, concise summary of the salient points. I think it makes worthwhile reading.

Autumn, 2015

Shift in Local Marine Ecosystems Has Me Worried

A Southern California kelp forest floor covered in almost nothing but brittle stars. Found near Santa Barbara Island, Labor Day Weekend, 2013.

I have been an observer of the ocean for 37 years now, privileged to check in on local marine life firsthand every few weeks or months. Fifteen years ago, changes I had already seen motivated me to volunteer long, hard days of work in the interest of creating marine reserves. Reserves are special areas in the ocean set aside, like parks, protected from human exploitation and preserved for human appreciation. Just five years after they were established, Central California's new Marine reserves yielded data indicating that they were working: fish were getting bigger and more diverse, ecosystems were looking more robust.

A patch of seafloor off Pacific Grove featuring a Rock Scallop and dozens of exposed sea urchins, February 2015.

In the last year, I've begun seeing patches of seafloor in Monterey Bay and Carmel Bay where that diversity is crashing. In Southern California's Channel Islands, we had often visited dive sites that had become "urchin barrens," areas where sea urchins had suddenly and inexplicably proliferated in huge numbers. The urchins gnawed away at the base of kelp plants, setting them adrift, and entire kelp forests floated away with the current. Urchin barrens are a phenomenon that has been studied by scientists for two or three decades now. The conventional wisdom has been that they could not form any areas where sea otters are present, since otters have enormous appetites and prey on urchins.

Early this year I began to see huge numbers of urchins out in the open with no protection from the voracious otters. I wondered whether some of my favorite dive sites were on the way to becoming urchin barrens, and also why otters were not feasting on the urchins?

Point Lobos State Marine Reserve is renowned for its lush and diverse marine life. Here, delicate California Hydrocoral grows on a ridge of granite.

The same day I first found urchins proliferating in Monterey Bay, I saw other patches of seafloor inundated even more completely by brittle stars. I had become acquainted with brittle stars as reclusive animals usually found cowering in the most protected spots, like under an abandoned abalone shell or beneath a rock. Finding one would be a treat, as they are delicate looking and often quite colorful. Now large patches of ocean bottom are looking like the underwater equivalent of cornfields, utterly dominated by a single species which has displaced dozens or hundreds of other colorful critters that used to be there. I had seen "brittle star barrens" in Southern California, too. Those observations went back 10 or 15 years, attended by puzzled conversations with fellow marine naturalists about what was going on, and why. Of course, cornfields are planted intentionally. These patches of brittle stars had arisen on their own. Whether the cause(s) of their appearance were entirely natural or a consequence of human activity, we could only guess.

Just yards away from the Hydrocoral, this patch of bottom in Point Lobos' Bluefish Cove is over run by brittle stars.

In August I dove at Point Lobos State Marine Reserve, a place I visit often. Diving there is a joy as the small marine reserve that had been created there in 1973 became vastly larger in 2007 as a consequence of the work in which I was a participant. Over 40 years of reserve status has allowed marine life in Point Lobos to become diverse, plentiful and large. Stories of divers petting fearless fish there are not uncommon. But deep on a favorite spot in Bluefish Cove, I found a patch of bottom also overrun with brittle stars and populated by almost nothing else. Whatever was giving rise to"brittle star barrens" in Pacific Grove was at work inside of Point Lobos, too.

These changes look, to this non-scientific observer, like major ecosystem shifts. Where I have seen them in Southern California, the new regimes of urchins and brittle stars have remained in place for years, resulting in impoverished marine life and sad days for divers who knew the areas in the full flower of their diversity. I am glad to say that several dives along the Big Sur coast south of Point Lobos conducted last June showed no signs of urchins or brittle stars taking over in those areas. Could the Monterey and Carmel marine ecosystems, and the dive sites enjoyed by so many, which I and others worked so hard to protect, be at risk from something we neither anticipated nor understand?

The mysteries posed by my recent observations remain mysteries for now. I have heard that some scientific investigation of this phenomenon is underway. I'll be checking into the current state of knowledge about it and writing more in the coming months. Keep an eye on my blog for further information.

|

|

| A Southern California kelp forest floor covered in almost nothing but brittle stars. Found near Santa Barbara Island, Labor Day Weekend, 2013. |

|

|

| A patch of seafloor off Pacific Grove featuring a Rock Scallop and dozens of exposed sea urchins, February 2015. |

In the last year, I've begun seeing patches of seafloor in Monterey Bay and Carmel Bay where that diversity is crashing. In Southern California's Channel Islands, we had often visited dive sites that had become "urchin barrens," areas where sea urchins had suddenly and inexplicably proliferated in huge numbers. The urchins gnawed away at the base of kelp plants, setting them adrift, and entire kelp forests floated away with the current. Urchin barrens are a phenomenon that has been studied by scientists for two or three decades now. The conventional wisdom has been that they could not form any areas where sea otters are present, since otters have enormous appetites and prey on urchins.

Early this year I began to see huge numbers of urchins out in the open with no protection from the voracious otters. I wondered whether some of my favorite dive sites were on the way to becoming urchin barrens, and also why otters were not feasting on the urchins?

|

|

| Point Lobos State Marine Reserve is renowned for its lush and diverse marine life. Here, delicate California Hydrocoral grows on a ridge of granite. |

The same day I first found urchins proliferating in Monterey Bay, I saw other patches of seafloor inundated even more completely by brittle stars. I had become acquainted with brittle stars as reclusive animals usually found cowering in the most protected spots, like under an abandoned abalone shell or beneath a rock. Finding one would be a treat, as they are delicate looking and often quite colorful. Now large patches of ocean bottom are looking like the underwater equivalent of cornfields, utterly dominated by a single species which has displaced dozens or hundreds of other colorful critters that used to be there. I had seen "brittle star barrens" in Southern California, too. Those observations went back 10 or 15 years, attended by puzzled conversations with fellow marine naturalists about what was going on, and why. Of course, cornfields are planted intentionally. These patches of brittle stars had arisen on their own. Whether the cause(s) of their appearance were entirely natural or a consequence of human activity, we could only guess.

|

|

| Just yards away from the Hydrocoral, this patch of bottom in Point Lobos' Bluefish Cove is over run by brittle stars. |

In August I dove at Point Lobos State Marine Reserve, a place I visit often. Diving there is a joy as the small marine reserve that had been created there in 1973 became vastly larger in 2007 as a consequence of the work in which I was a participant. Over 40 years of reserve status has allowed marine life in Point Lobos to become diverse, plentiful and large. Stories of divers petting fearless fish there are not uncommon. But deep on a favorite spot in Bluefish Cove, I found a patch of bottom also overrun with brittle stars and populated by almost nothing else. Whatever was giving rise to"brittle star barrens" in Pacific Grove was at work inside of Point Lobos, too.

These changes look, to this non-scientific observer, like major ecosystem shifts. Where I have seen them in Southern California, the new regimes of urchins and brittle stars have remained in place for years, resulting in impoverished marine life and sad days for divers who knew the areas in the full flower of their diversity. I am glad to say that several dives along the Big Sur coast south of Point Lobos conducted last June showed no signs of urchins or brittle stars taking over in those areas. Could the Monterey and Carmel marine ecosystems, and the dive sites enjoyed by so many, which I and others worked so hard to protect, be at risk from something we neither anticipated nor understand?

The mysteries posed by my recent observations remain mysteries for now. I have heard that some scientific investigation of this phenomenon is underway. I'll be checking into the current state of knowledge about it and writing more in the coming months. Keep an eye on my blog for further information.

Multi-Generational Whale Watching as Humpbacks Feast in Monterey Bay

|

|

| Five Humpback Whales, lunge-feeding near Moss Landing on September 18, 2015. |

On Wednesday, September 16 my wife Chris went for a walk along West Cliff Drive, near the iconic lighthouse in Santa Cruz. If you were lucky enough to be there that day you saw what she did: Humpback whales just a few feet off of the beach lunging through schools of anchovies with their mouths agape. The local paper wrote about the amazing event. I went with her following day, camera in hand, hoping for a repeat performance. But the anchovies and almost all of the whales had moved on.

The next day my mother (fresh from celebrating her 80th birthday) was visiting. My son had no school, and Chris suggested we all get up early and ride my dive boat out into Monterey Bay in search of whales. So with the 12-year-old confidently manning the helm, we motored westward from Moss Landing. Just outside the harbor we encountered an old friend carrying a couple passengers on a similar expedition. None of us had long to wait. Just a few miles offshore we saw the foggy puffs of whale blows on the horizon. Flocks of seabirds concentrated above schools of small fish, anchovies we thought. Then, suddenly emerging from the ocean were the mouths of four or five Humpback whales, water streaming from between their jaws. Water passed through the whales' baleen but the little fish could not. Humpbacks have no teeth, they use baleen to strain small fish and even tinier krill from enormous mouthfuls of seawater. I'd seen whales in the Bay before, and I knew their feeding biology well from reading about it, but I'd never been able to watch whales feeding before. I was thrilled that three generations of my family could share the marine magic.

My shutter clicked away furiously as my mother gasped and then squealed with delight. Despite eight decades of life, it was her first close encounter with these magnificent giants of the sea. Whales are rarely sighted near her home in Ohio. Once again, I was glad to live in Central California.

Warm Water Again: El Niño Says, "I'm Baa-aack"

Like that ominous, unstoppable character played by Jack Nicholson in The Shining, El Niño is preparing to launch its mischief on the world this winter. NOAA is estimating a 95% chance that El Niño conditions will continue through this spring. Unlike the demon played by Nicholson in that 1980 movie, this year's El Niño may be welcomed in. It could bring a wet winter to California, potentially relieving an extreme, years-long drought. But if the much-needed rain returns to California, it could also be at the expense of parching places like Australia and Indonesia, which get drier in El Niño years.

Last year, we saw a "mini El Niño." Ocean temperatures in a narrow band along California's coast spiked as much as 10°F above normal. I wrote then that the energy contained in that warm water would produce a wet winter last year. For about a month, that prediction looked good as rainfall in December 2014 ran about 150% of average, before the rains failed. This year, temperatures are not quite as high but the warm water is spread across a huge expanse of the Pacific Ocean, meaning that a longer and more powerful El Niño is more likely.

El Niño only "opens the door" to wet weather in California. Here in Santa Cruz County, the El Niño event that began in 1981 caused devastating floods in the first week after New Year's of 1982. Even though the El Niño events of 1995 and '98 were more powerful than that of 1981, they produced floods that were not as severe, locally, as those of 1982. NOAA currently estimates that this year's event is as strong or stronger, globally, as any on record. What that means for any locality is impossible to predict. We are hoping for a strong rainy season, of course, to end the drought here. But as a wise teacher used to tell me, "Watch what you wish for, you're liable to get it."

Warm Water: Message in a Bottle?

|

|

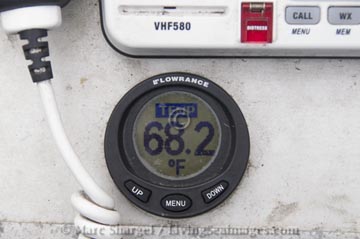

| The warmest surface temperature I’ve ever seen in Central California, a couple hundred yards off Capitola Beach, August 2, 2014. |

The sign I’m interpreting is the very warm water temperatures in the Pacific just off our beaches. By late July, surface temperatures off Point Lobos were above 60°F. In early August, the water in the middle of Monterey Bay was 64°F, easily 10 degrees above “normal.” Surface water south of Point Lobos was 61-63°F, and those temps were consistent down to forty feet deep that day. Dive buddies who visited the islands off San Diego over the Labor Day weekend reported 73°F, more than five degrees above typical readings.

When you put a pot of water on the stove, even before it boils it begins to steam. The warm ocean water off our coast will evaporate and form more clouds than cooler water would. That would make us think more rain will fall somewhere. The last time I saw the ocean get this warm was October of 1997. That month, while diving in Monterey, I photographed blacksmith, a kind of fish usually only found well south of Santa Barbara. The water was around 65°F. Four months later, in February of 1998, extremely heavy rains swelled the San Lorenzo and Pajaro Rivers so much that they caused major flooding.

|

|

| Blacksmith, a typical Southern California fish, photographed at the Monterey Breakwater in October of 1997. The water was about 65°F. |

I don’t know if this winter’s rains will even be above average. Climate scientists tell us that predicting the El Niño weather pattern that brings heavy rain to California depends on the warmth of water all across the Pacific. And they differ on interpreting the current indications for an El Niño. Even if El Niño does materialize, the rains could pass us by. But our local ocean has been “cooking up” interesting consequences: see our next article.

Warm Water Brings Unusual Sightings

|

|

| A large Ocean Sunfish or Mola mola. Surely this is one of the oddest creatures on the planet. It looks like somebody began to draw a fish, but forgot the back half of the body. |

One immediate bonus brought by this season’s warm water was the appearance of some infrequent visitors. In late July and early August we spent three days on the water in the space of a week and a half. On each day we spotted a certain type of fin lazily waving above the surface of the smooth water. The fins were big, but the wrong shape to belong to a shark or dolphin. We approached carefully and each time discovered a large Ocean Sunfish or Mola mola. Small molas are frequently seen in the fall in our area. In 2012 we had an amazing dive with over a dozen of them, including one that appeared to have been bitten by a shark. We wrote about that day in our blog, too. We know that sea lions prey on small molas, we’ve even photographed the action. But the ones we saw this summer were about as big as a human, we estimated five feet long. We saw them in Carmel Bay, and to the south of Point Lobos, and out in the middle of Monterey Bay.

|

|

| Velella velella, the "By-The-Wind Sailor," a peculiar floating jelly. Like rudderless sailboats, these landed in the kelp in Whalers' Cove. |

We saw the big molas close by another unusual visitor, a small jelly called the By-the-Wind Sailor, Velella velella. Velellas are the strangest of jellies. They have more in common with boats than with other jellies: they are oval shaped, about four inches long, and float on the surface of the ocean. They have a texture more like plastic than jello. Unlike other jellies that “swim” underwater by pulsing their bells, the body shape of velellas makes them a sailboat. The upper part of the velella, which catches the wind, resembles the sail of a boat tacking across the wind. The lower part, which is below the surface, is a hanging ring of short, blue tentacles. They use their tentacles as do the more typical jellies, to sting and gather food. Usually when you spot one velella, you’ll be able to find many more. Sometimes thousands more. On August 1st we discovered velellas coating patches of the ocean’s surface.

|

|

| One of the many patches of the ocean off Carmel that was covered by Velellas in late July. |

Now why were we seeing velellas and molas near each other? As my boat drifted near a pair of five-foot molas I found out. I stood watching as one mola swam slowly, straight toward the boat. I could see it below the surface, angling upward. As its head reached the surface, the mouth opened and gently sucked in a velella. The molas had come in to take advantage of an enormous feast!

|

|

| A pair of Orcas headed for a Sea Lion haul out in British Columbia. Time for lunch? |

Our summer of encounters with unusual visitors reached its peak after our dives on August 1st. Heading homeward, we spotted two tall, black fins about a mile off the Carmel Highlands. Orcas! A pair of them, cruising southward. At one point they surfaced so close to the boat that we heard the blows almost before we saw the fins. We had seen a humpback whale in the area, too, but the orcas did not seem to be hunting it, they just kept traveling.

Orcas are occasional visitors in Central California, but regular residents off the islands of northern Washington State and British Columbia. In September, near the northern end of Vancouver Island, we watched a trio of Orcas hunting Steller Sea Lions.

Marc Shargel releases a new publication.

Yesterday’s Ocean: A History of Marine Life on California’s Central Coast

Now Available FREE

Marc Shargel's newest, much-awaited publication has just been released. Yesterday’s Ocean: A History of Marine Life on California’s Central Coast is now available in e-book form. Yesterday’s Ocean traces the arc of human exploitation of several types of marine life, with emphasis on species native to the Monterey Bay and surrounding waters. The stories are told in pictures as much as words, with some photos by the author, but many more from historical archives. Imagine piles of abalone shells taller than a man, or stacks of sharks caught for the vitamin A in their livers. Where would you look to find a billion pounds of sardines? They're all inside Yesterday’s Ocean.

Marc Shargel's newest, much-awaited publication has just been released. Yesterday’s Ocean: A History of Marine Life on California’s Central Coast is now available in e-book form. Yesterday’s Ocean traces the arc of human exploitation of several types of marine life, with emphasis on species native to the Monterey Bay and surrounding waters. The stories are told in pictures as much as words, with some photos by the author, but many more from historical archives. Imagine piles of abalone shells taller than a man, or stacks of sharks caught for the vitamin A in their livers. Where would you look to find a billion pounds of sardines? They're all inside Yesterday’s Ocean.

Best of all, the e-book of Yesterday’s Ocean is available to you free of charge, right now. You can read it on-line using most any web browser. A version for mobile devices is in development. If you'd like to be notified when the mobile version is available, please Subscribe to our Newsletter.

Yesterday’s Ocean has attracted a flurry of media attention. Marc was interviewed for an installment of the Thank You Ocean Podcast. A slide show came out on the Ocean Conservancy website, and the Natural Resources Defense Council's blog included a recent article.

Yesterday’s Ocean is Marc Shargel's fourth publication, but the first to cover his home area of Central California. Previously, he released three printed coffee-table books in the Wonders of the Sea series, covering each region of the state except Central California. Shargel hopes to produce a fourth book in that series, on Central California.

Coastal Cleanup First Friday Community Art Exhibit.

Coastal Cleanup Day is held in our area each year in mid-September. We've participated in the past by doing underwater recovery of trash from the seafloor. This year we're contributing to the Coastal Cleanup First Friday Community Art Exhibit at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History. The exhibit features twelve local artists who work on ocean life and ocean-related subjects. We've contributed three framed photographs to the exhibit

The exhibit will hang in the main auditorium of the MAH from the First Friday in September (the 6th) through the 22nd. On Friday evening the 6th, the museum is hosting an opening event with many of the artists, including Marc Shargel, present. The event is part of First Friday Santa Cruz, which is a monthly art event at multiple venues throughout the county. The opening reception at MAH is 5pm to 9pm, Friday evening September 6 and admission to the museum that night is free. The Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History is at 705 Front Street, in the heart of downtown.

Coastal cleanup is a great opportunity to help our local ocean very directly: with your own hands. We know the importance of recapturing trash from direct observation. Just a few days ago, miles off the Southern California coast, we saw a tattered bit of duct tape drifing through a kelp forest. At first we wondered if it was a jelly we weren't familiar with. Small pink fish called señoritas seemed to be feeding on it, as they do on many jellies. Realizing it was human trash, we swam into the cluster of señoritas and collected their would-be meal. Plastics have been identified as a lethal cause of digestive tract blockage in some sea birds; we hope the little fish didn't ingest much of the duct tape. "Coastal cleanup" is a pretty regular activity for us: most days on the ocean we pluck at least one bit of drifting plastic trash from the surface of the ocean. We hope you'll come see the art exhibit at MAH, and take part in the coastal clean up event, which is on Saturday, September 21 this year.

August 19, 2013

Marc Shargel featured on the Thank You Ocean Podcast and other online media.

Thank You Ocean is a five-year-old podcast that does a wonderful job of informing the public on ocean-related news and issues. Veteran environmental reporter Jerry Kay does the interviews and he and his production team have reached a high level of quality with the series.

The current issue edition of Thank You Ocean features Marc Shargel talking about why he created Yesterday’s Ocean: A History of Marine Life on California’s Central Coast. Jerry Kay's interview was right on point, the editing helped convey the message in under five minutes. The visuals that illustrate the interview give you an accurate sample of the experience you'll have when you look inside Yesterday’s Ocean.

Here are some more media items:

- The Huffington Post's blog page recently included an article about Yesterday’s Ocean.

- Yesterday’s Ocean is the subject of a slide show just posted by The Ocean Conservancy on their Blog Aquatic page. The slide show summarizes the story in the Yesterday’s Ocean e-book in a series of less than two dozen visuals.

- Yesterday’s Ocean is also subject of an article on the Natural Reources Defense Council's "Switchboard" blog.

Thank You Ocean is a five-year-old podcast that does a wonderful job of informing the public on ocean-related news and issues. Veteran environmental reporter Jerry Kay does the interviews and he and his production team have reached a high level of quality with the series.

The current issue edition of Thank You Ocean features Marc Shargel talking about why he created Yesterday’s Ocean: A History of Marine Life on California’s Central Coast. Jerry Kay's interview was right on point, the editing helped convey the message in under five minutes. The visuals that illustrate the interview give you an accurate sample of the experience you'll have when you look inside Yesterday’s Ocean.

Here are some more media items:

- The Huffington Post's blog page recently included an article about Yesterday’s Ocean.

- Yesterday’s Ocean is the subject of a slide show just posted by The Ocean Conservancy on their Blog Aquatic page. The slide show summarizes the story in the Yesterday’s Ocean e-book in a series of less than two dozen visuals.

- Yesterday’s Ocean is also subject of an article on the Natural Reources Defense Council's "Switchboard" blog.

Schools of Young Rockfish Arriving in Historic Numbers.

Beginning in May of 2013 we started seeing extraordinary numbers of tiny rockfish, less than two inches long. The numbers have been so enormous that there were clouds of little fish in some areas. Juvenile Blue Rockfish have been the most commonly seen, but we've noted five or six different species at least. In June we spent three days diving off the remote Big Sur coast and were lucky to enounter some of the clearest water we'd ever seen in Central California. The combination of rare ocean conditions and rare marine life abundance made for an amazing trip. The underwater vistas looked more like the Carribean or the Indo-Pacific than what we're used to around here. Of course, the water temperature, as cold as 48F, brought us back to reality. We've captured and posted over 125 images of this historic event so far.

Rockfish spawn and hatch once a year; the young appear in the spring. Fish of just a couple inches in length have hatched within the last few months; biologists refer to them as young of the year (YOY). We've observed YOY Rockfish almost every year for decades, in numbers of up to a few dozen. Just once, in 2007, diving at Shelter Cove on the "Lost Coast" of Far Northern California, we encountered a cloud of YOY Rockfish that numbered a few thousand. This year we've been seeing them in the tens of thousands. In fact, 2013's influx of young fish anything we've seen in 35 years, and even anything we've heard about.

This year's new recruits have been widespread and varied. We've seen clouds of YOY from Carmel Bay all the way down the Big Sur coast as far as Cape San Martin (north of San Simeon), at every spot we've gotten in the water. Reports of similar clouds of fish have come from Monterey, and there has been evidence of that similar activity has been going on as far north as Año Nuevo, north of Santa Cruz. We've identified juvenile Blue Rockfish as the most prominent species in this year's event, but we've also seen the young of the scarce Canary Rockfish, Half-banded Rockfish (which live so deep as adults that we'd never seen one before), and at least one of the three species that are impossible to distinguish as YOY. These are the Kelp, Gopher, and Black-and-Yellow Rockfish.

This year's new recruits have been widespread and varied. We've seen clouds of YOY from Carmel Bay all the way down the Big Sur coast as far as Cape San Martin (north of San Simeon), at every spot we've gotten in the water. Reports of similar clouds of fish have come from Monterey, and there has been evidence of that similar activity has been going on as far north as Año Nuevo, north of Santa Cruz. We've identified juvenile Blue Rockfish as the most prominent species in this year's event, but we've also seen the young of the scarce Canary Rockfish, Half-banded Rockfish (which live so deep as adults that we'd never seen one before), and at least one of the three species that are impossible to distinguish as YOY. These are the Kelp, Gopher, and Black-and-Yellow Rockfish.

Rockfish have reproductive success only when oceanographic conditions are just right: water temperature, currents, availability of tiny planktonic food all have to favor their survival. This year, apparently, we've had a "perfect storm" of factors aligning to permit a Rockfish population boom. Because human consumption has affected many species, and depleted some quite badly, this is a very good thing for our ocean overall. Of course the fertility of rockfish also depends on having a significant breeding population somewhere. Recently, scientists have discovered that many fish, including rockfish, become more fertile they older they get. Great-Grandmother rockfish produce clutches of eggs many times larger than their younger counterparts. So the fact that some of the little fish appearing this year will have the chance to live to old-age, within marine protected areas, is also a very good thing for the ocean.

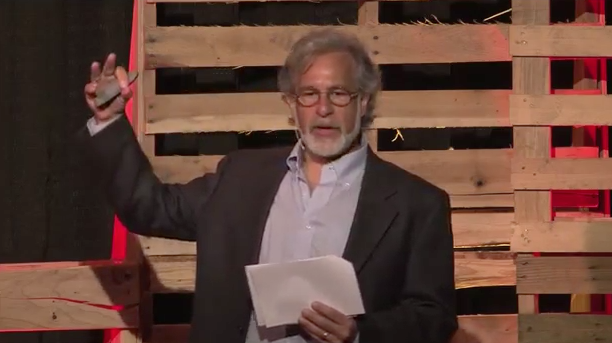

Video of Marc Shargel's talk at TEDx Monterey is online.

Video of Marc Shargel's talk at TEDx Monterey is now available online.

On April 13 Marc Shargel delivered a talk at the TEDx Conference in Monterey, CA. Entitled Yesterday’s Ocean, like his new e-book, the talk presented stories of marine life and its human use through 200 years of Central California Coast history.

In response to many requests we've received for access to the video we are, at last, able to provide this link.

A presentation of images at Aquarium of the Bay

Pier 39 San Francisco California

Saturday January 19, 2013 at 12:00 noon

In celebration of Underwater Parks Day in California, the Aquarium of the Bay at Pier 39 in San Francisco will be hosting a presentation by photographer and author Marc Shargel on Saturday, January 19, 2013. From the comfort of your chair in the Aquarium's Bay Theater, Shargel will transport you with photographic visions from beneath many of our state’s newly protected underwater parks. California is the first state in the country to establish a state-wide network of marine protected areas, a fourteen-year effort that just concluded one month ago.

For complete information, including links to a map, a free sea lion tour, and how to get a 50% discount on admission to the the Aquarium of the Bay at Pier 39, see my events page.

Back Where I Started

Among my most vivid childhood memories are days spent on the beach at Lake Erie. Yes, I grew up in the Cleveland area. That was in the 1960s when industrial pollutants were turning the Great Lake into what would soon be called a "dead body of water." In 1969, the oliy water of the Cuyahoga River, which empties into the lake in downtown Cleveland, turned a dock fire into a conflagration. The event lives forever in Randy Newman's musical lampoon, Burn On. My grandmother and I were sometimes turned back from walks along Lake Erie's shore by the stink of rotting fish that would periodically wash up on the shore. As she read books by Rachel Carson, I was getting a first-hand lesson in environmental thinking.